Parvo in Pups

Canine parvovirus (CPV), commonly referred to as parvo, is one of the most serious viruses that puppies, adolescent and mature dogs can contract. Why? Because this potentially fatal virus is especially difficult to kill, is able to exist for an extremely long time in the environment, and is shed in very large quantities by infected dogs.

There are two slightly different strains of canine parvovirus: CPV-2a and CPV-2b. While both cause the same disease, CPV-2b is associated with the most severe form. Thankfully, however, parvo vaccines such as DA2PPC and DHPP afford dogs protection against both of them.

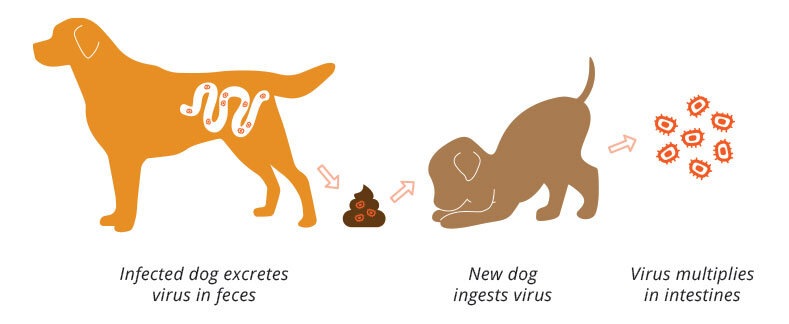

Direct contact between two dogs isn’t needed for the virus to spread. In fact, one of the most common ways for a susceptible (unvaccinated) dog to become infected is by ingesting the feces of an already-infected dog. But due to its environmental stability, this notorious virus can just as easily be transmitted through the paws and hair of an infected dog, an unsuspecting person’s shoes and clothes, as well as any surface or object that’s been unknowingly contaminated.

Infected dogs will usually become ill within six to ten days of exposure. The virus is carried to the intestine where it invades the intestinal wall, causing an inflammation, and although the symptoms may vary, severe vomiting and diarrhea are not only the first but also the most consistent and common signs of infection. The ailing dogs’ diarrhea will often have a very strong smell, may contain large amounts of mucus, and may or may not contain blood. Some affected dogs may also stop eating, appear listless and depressed, and run a fever.

While parvo can affect dogs of all ages, it most commonly affects unvaccinated dogs under the age of one. Puppies younger than five months are usually the most severely affected and the most difficult to treat. Any unvaccinated puppy who is vomiting, has uncontrolled diarrhea, or both, should immediately be brought to the vet and tested for CPV.

A fecal ELISA test (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) is the most common way of diagnosing a dog suspected of having parvo, requires a fecal swab, and takes about 10 minutes. Although the test is accurate, a negative result doesn’t automatically rule out parvo in a symptomatic dog since he may not have been shedding the viral antigen at the time the test was taken. If this is the case, to err on the side of caution, he should be re-tested.

Sadly, there’s no treatment to date that can kill the virus once it infects a dog. And while the virus itself isn’t the direct cause of a dog’s death, it targets the epithelium of the small intestine, the lining that helps to absorb nutrients and provides a crucial barrier against fluid loss and bacterial leakage into the rest of the body. This leakage coupled with the intestinal damage, results in severe dehydration (water loss), electrolyte (sodium and potassium) imbalances, and an infection in the bloodstream (septicemia). If septicemia develops, a dog is more likely to die.

Therefore, the sooner emergency measures are implemented in a hospital setting, the greater a dog’s chances of survival. The first step involves reversing his dehydration and correcting his electrolyte imbalances through the use of an IV (intravenous fluid) drip containing electrolytes. In more severe cases, plasma transfusions may be administered as well. He’ll be given antispasmodic drugs to inhibit his diarrhea and vomiting along with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs to either prevent or control septicemia.

Fortunately, most dogs suffering from parvo will recover if aggressive treatment is started promptly -- before severe dehydration and septicemia occur. For puppies, however, if they haven’t improved by the third or fourth day of treatment, their prognosis is poor.

Vets everywhere strongly advise all responsible dog owners to protect their precious pets against CPV by having them vaccinated. Puppies will receive a parvovirus vaccination as part of their multiple-agent vaccine series, given at 8, 12 and 16 weeks of age. In some high-risk situations, vets will administer the vaccine at two-week intervals with an additional booster given at between 18 and 22 weeks of age. After that initial series of vaccinations, boosters will be required on a regular basis. If an approved three-year parvovirus vaccine was used, boosters should be routinely administered every three years.